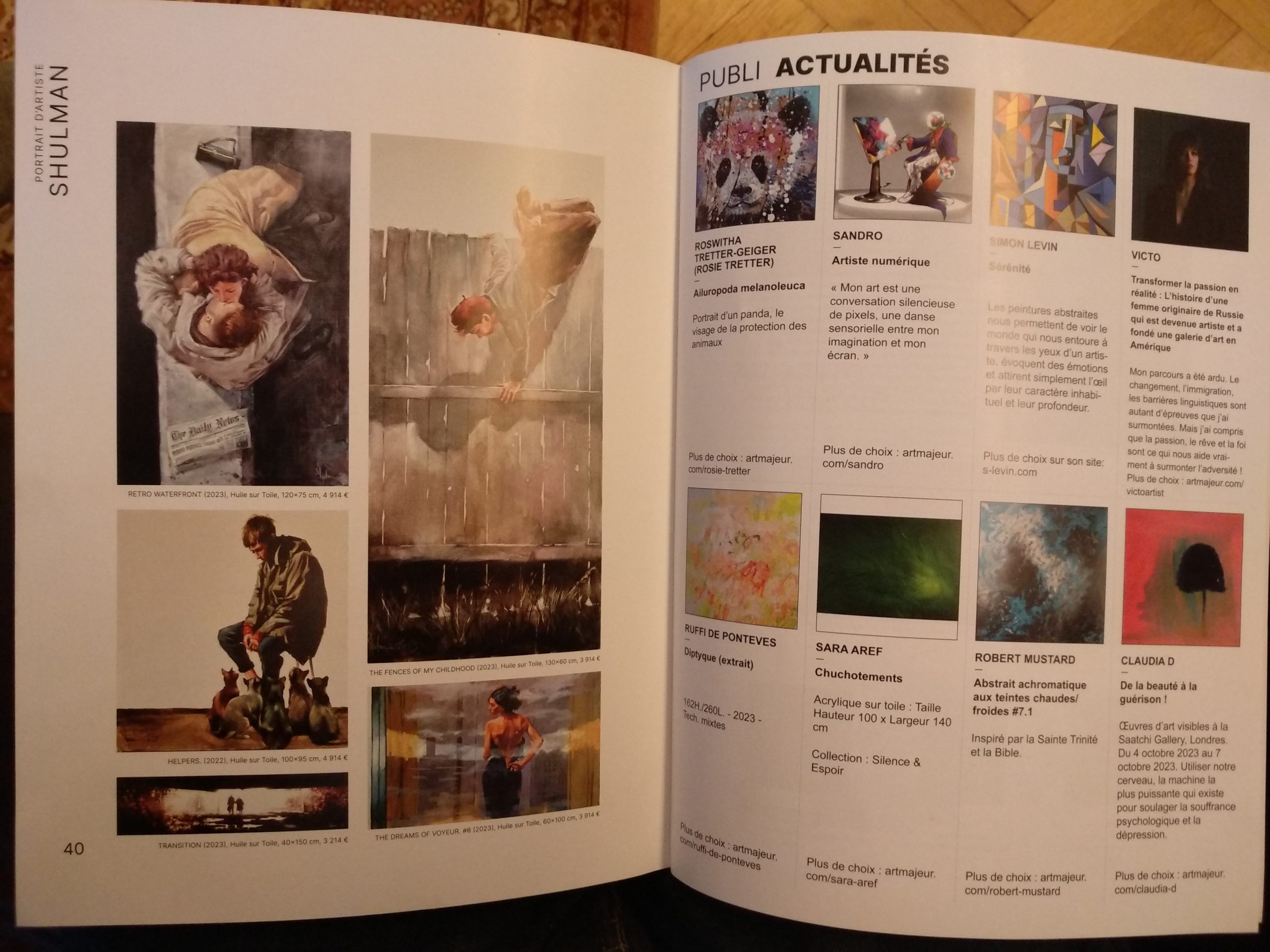

ArtMajeur: SHULMAN – Portrait d’artiste

A Russian Painter’s Vision of the World Through Realism – ArtMajeur Publication

Read it in English

SHULMAN Igor Andrianov Shulman, peintre né en 1959 en Russie, où il a étudié à l’école d’art A. G. Venezianov, vit et travaille à Prague depuis 1999, un lieu qu’il considère comme une immense source d’inspiration.

Cependant, lorsque nous interrogeons l’artiste, il nous révèle qu’il a en réalité commencé sa carrière de peintre bien plus tôt, c’est-à-dire dès son plus jeune âge, en dessinant toujours. Malgré une pause créative de quatre ans qui a suivi les études susmentionnées, l’incompatibilité présentée entre l’école et le processus créatif a généré une suspension de l’activité picturale, qui s’est déroulée de 1890 à 1984, interrompant momentanément toutes ses recherches figuratives.

Shulman prétend faire partie d’une race d’artistes en voie de disparition, qui ont choisi d’expliciter leur vision du monde à travers un réalisme qu’il définit lui-même comme primitif, une sorte de carapace qui, comme tant d’autres, fait partie du désormais long et le vocabulaire connu de l’art. La décision d’adhérer à ce point de vue particulier est venue après des années d’études, au cours desquelles l’artiste s’est essayé à de multiples formes d’art, qui, tout en s’étendant de la mosaïque à l’illustration, l’ont conduit au royaume du pinceau.

Les protagonistes de l’investigation picturale de Shulman varient selon les circonstances et les intérêts du peintre, qui préfère immortaliser le monde à travers un langage simple et clair, visant, comme il l’a déclaré lui-même, à ne pas bouleverser le point de vue des personnes plus âgées et traditionalistes. Dans le cas des sujets humains, Shulman s’efforce de les saisir “dans leur environnement, leurs habitudes, leur mode de vie, ainsi que leur interaction avec le monde et les uns avec les autres”.

Le peintre, soucieux de saisir la figure humaine, se pose également cette question: “Qu’y a-t-il dans la tête des gens?”, ainsi que mille autres, car il a intérêt à s’interroger sur tout ce qu’il observe.

L’environnement urbain dans lequel évoluent ces figures, parfois animales, reste en retrait, car le peintre soutient qu’une ville ne peut exister sans la vie, qui, materialisée dans les actions et les relations des etres vivants, l’anime.

Les animaux se rapprochent souvent de la figure humaine, car l’artiste les a toujours eus chez lui, se trouvant ainsi en difficulté à imaginer la routine sans leur présence.

Shulman, propriétaire d’un carlin nommé Monica, affirme que la relation homme-chien peut enrichir les deux, ce qui le fait souvent opter pour une peinture visant à unir les hommes et les animaux sur le support.

Parfois, le binôme homme-chien, homme-chat, etc., s’accompagne d’attitudes résolument introspectives de la personne représentée, un aspect qui ressort parce que l’artiste est attiré par les états mentaux de l’être humain, à tel point qu’il affirme que “l’intériorité de quelque chose est plus proche de lui que l’extérieur”.

Cependant, tout reste un peu relatif, puisque les messages lancés par l’artiste restent majoritairement multiples et changeants, étant extrêmement liés aux sensations que l’artiste tire de l’observation du contenu d’une image, prêt, à chaque fois, à synthétiser une perception réaliste, et, en même temps, principalement émotionnelle et subjective.

Igor Andrianov Shulman, a painter born in 1959 in Russia, where he studied at the A.G. Venezianov art school, has been living and working in Prague since 1999, a place he considers a huge source of inspiration.

However, when we question the artist, he reveals to us that he actually began his career as a painter much earlier, that is to say from a very young age, drawing everything and always. Despite a four-year creative break that followed the aforementioned studies, the incompatibility presented between the school and the creative process generated a suspension of pictorial activity, which took place from 1890 to 1984, momentarily interrupting all his figurative research.

Shulman claims to be part of a race of artists in the process of disappearing, who have chosen to express their vision of the world through a realism that he himself defines as primitive, a sort of shell which, like so many others, is part of the now long and well-known vocabulary of art. The decision to adhere to this particular point of view came after years of study, during which the artist tried his hand at multiple forms of art, ranging from mosaic to illustration, leading him to the realm of the brush.

The protagonists of Shulman’s pictorial investigation vary according to the circumstances and interests of the painter, who prefers to immortalize the world through a simple and clear language, aiming, as he himself has declared, not to upset the point of view of older and more traditional people. In the case of human subjects, Shulman strives to capture them “in their environment, their habits, their way of life, as well as their interaction with the world and with each other.”

The painter, concerned with capturing the human figure, also poses this question: “What is in people’s heads?”, as well as a thousand others, because he is interested in questioning everything he observes.

The urban environment in which these figures, sometimes animals, evolve, remains in the background, as the painter maintains that a city cannot exist without life, which, materialized in the actions and relations of living beings, animates it.

Animals often approach the human figure, as the artist has always had them at home, finding it difficult to imagine the routine without their presence.

Shulman, the owner of a pug named Monica, claims that the human-dog relationship can enrich both, which often leads him to opt for a painting aimed at uniting humans and animals on the support.

Sometimes, the human-dog, human-cat, etc., pair is accompanied by resolutely introspective attitudes of the person represented, an aspect that stands out because the artist is attracted to the mental states of the human being, to such an extent that he affirms that “the interior of something is closer to him than the exterior.”

However, everything remains a bit relative, since the messages launched by the artist remain mostly multiple and changing, being extremely linked to the sensations that the artist draws from the observation of the content of an image, ready, each time, to synthesize a realistic perception, and, at the same time, mainly emotional and subjective.

ISSN: 2556-6946